The earth is the centre of the universe – what a crazy thought, right? But during the various transitions from the geocentric, to the heliocentric and, more recently to a relativistic model of our place in the cosmos, many forward thinking persons lost their place in society, their livelihoods, their lives. Great efforts were made to maintain a status quo on this question, to the level of absurdity! It is still going on now. Whether in astronomy or in mathematics, medicine or architecture, the stranglehold of conservative thinking has significantly hampered progress.

The earth is the centre of the universe – what a crazy thought, right? But during the various transitions from the geocentric, to the heliocentric and, more recently to a relativistic model of our place in the cosmos, many forward thinking persons lost their place in society, their livelihoods, their lives. Great efforts were made to maintain a status quo on this question, to the level of absurdity! It is still going on now. Whether in astronomy or in mathematics, medicine or architecture, the stranglehold of conservative thinking has significantly hampered progress.

I don’t know about you, but whenever I dig into the Ptolemaic model for stellar mechanics, I become completely lost. Of course, I could also say that the I had a similar experience when I worked my way through general relativity! But the complexity of the Ptolemaic model was quite profound, and it was based on some very basic assumptions that derived from Aristotelian philosophy. So a fundamental axiom that was based on a narrow interpretation of the human condition drove the creation of a model that could never really describe what was actually going on. What? And the model was declared wisdom for a thousand years?

What does a “geocentric” type model in economics look like? Have we based the fundamentals of our economic models on a basic interpretation that is flawed? To be sure, the economic model attempts to describe a human activity, so it might make some sense to put the human condition at the centre of it. But what is really at the centre of the mainstream economic models? Isn’t the classical model of economics centred on the idea of institution – households, enterprises, municipalities, nations? How is monetary policy driven, except through the institutions?

What does a “heliocentric” model look like? What is the centre around which everything else revolves? We could argue that the fundamental component of any economic system is human value. This leads to a number of conclusions, including the idea that the commoditisation of human value is a great source of evil in the world, driving things like slavery, war, prostitution. But, as in the astronomy debate, it can reveal important concepts upon which to base a real model for economics.

What does a relativistic model of economics look like?

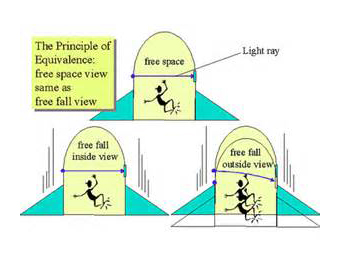

General relativity describes the effect of gravitation in the universe. One of its fundamental insights is that gravitation is experienced when the natural world-line of a particle is disrupted. We observe weight, not because it is the natural state, but because the natural state has been disrupted. We are experiencing the effects of an acceleration in the opposite direction of the natural fall of the space-time matrix. So our observable world is not the natural state of the world, but the altered state. It is even more interesting to think of this in terms of time. We experience time purely as an altered state of the infinite. Contemporary physics describes the mechanisms of how we experience these fundamental alterations as broken symmetry. And we build the most expensive machinery in history to help us see the point of disruption.

General relativity describes the effect of gravitation in the universe. One of its fundamental insights is that gravitation is experienced when the natural world-line of a particle is disrupted. We observe weight, not because it is the natural state, but because the natural state has been disrupted. We are experiencing the effects of an acceleration in the opposite direction of the natural fall of the space-time matrix. So our observable world is not the natural state of the world, but the altered state. It is even more interesting to think of this in terms of time. We experience time purely as an altered state of the infinite. Contemporary physics describes the mechanisms of how we experience these fundamental alterations as broken symmetry. And we build the most expensive machinery in history to help us see the point of disruption.

Can we imagine an economic model that would reject the hoary old concepts of classical economics and, building on the basis of a human value centred model, describe the natural economic field? What if the fundamental unit of human output became the form against which we measured things like inflation? It might be fruitful to examine some fundamental human output, such as what is seen in the performing arts, or in the analytic professions, such as the law or medicine, where there are no substantial shortcuts or productivity gains that arise as a result of new technology. Against such a universal measurement, we might start to see the world of productivity rushing by, ever accelerating. If the cost of hearing a single violin played well is compared, from the time of Vivaldi until now, how would we then see inflation, or monetary policy?

This analysis has been explored, in the Annales School in France, for example, or in Baumol’s Cost Disease theory. It may also begin to answer one of my own pet interests, the place of human rights in economic transactions. But most importantly, it may start to drag economic thinking out of the dark ages and through a greater enlightenment into a post-enlightenment world. We could use a little more of an enlightened view and a little less Spanish Inquisition in this very human discipline.